Another great reflection on the conference here, from Cath Feely

Objects and remembering

This is a great overview of the conference by Emma-Jayne Graham, who talked to us about votives – terracotta babies given to the Gods

Last Friday (20th June) I attended a conference on ‘Objects and Remembering’ at the University of Manchester. The event brought together people working on the relationship between objects and memory from a number of different perspectives – archaeology, history, museum and heritage studies, forensics and geology. It was a highly stimulating day, full of lively discussion and a realisation that many of us were headed in the same direction, even if we were taking very diverse routes in our attempts to get there. What was our shared goal? To better understand both the way in which objects are implicated in memory-making, and the consequences of memory for the meaning-making associated with objects.

Last Friday (20th June) I attended a conference on ‘Objects and Remembering’ at the University of Manchester. The event brought together people working on the relationship between objects and memory from a number of different perspectives – archaeology, history, museum and heritage studies, forensics and geology. It was a highly stimulating day, full of lively discussion and a realisation that many of us were headed in the same direction, even if we were taking very diverse routes in our attempts to get there. What was our shared goal? To better understand both the way in which objects are implicated in memory-making, and the consequences of memory for the meaning-making associated with objects.

Several themes emerged over the course of the day that I have continued to reflect upon, especially in terms of their relevance to the study of votive practice: authenticity (of objects, experience, and memory); the creation and…

View original post 1,112 more words

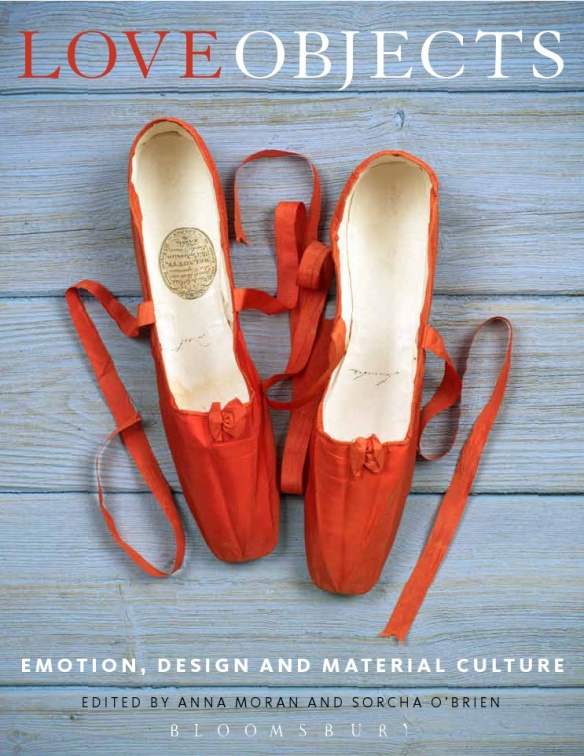

Love Objects: Emotion, Design and Material Culture

This is a guest post from Sorcha O’Brien, (Kingston University) and Anna Moran (National College of Art and Design, Dublin). They talk about their book Love Objects: Emotion, Design and Material Culture.

Bringing together a range of material from design history, material culture, design practice and anthropology, Love Objects: Emotion, Design and Material Culture looks beyond the obvious symbols of love, to investigate the different ways that we relate to objects and use them, not just as ‘signifiers’, but as actors to help negotiate our relationships with others.

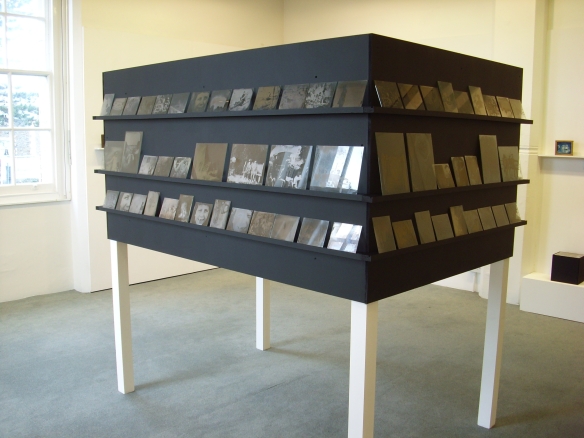

Several of the essays touch on family relationships mediated by objects, but two in particular look at the practice of using objects to perform cathartic acts of remembrance. Christina Edwards’ essay is a meditation on how she took a collection of family photographs and reworked them in the darkroom after her parents’ death; she meditates on loss and grief, as well as the act of creating something new. Catherine Harper’s essay takes her memory of her grandmother’s quilt as a starting point. Through her own textile practice she makes a surprising discovery about how ideas and craft practices are transmitted through generations of women. Both of these essays recognise that it is not the objective quality or sophistication of the object that is important in creating a vessel for memory and inspiration, but their ability to prompt new considerations and revaluations of the past.

Christina Edwards, ‘Material Memories’ exhibition, School of Art, University of Wales, Aberystwyth, February 2008.

The re-evaluation of the past is central to Jane Hattrick’s essay on her work with the archive house of London fashion designer Norman Hartnell. Her working relationship with the personal possessions painstakingly accumulated over a lifetime makes them much more than just the raw material of historical research. Bruce Davenport’s work on ‘magical touching’ is relevant here, although Hattrick’s approach to both her material and her own reactions to them situates the discussion of sexuality and archival practice within a current debate in design history revolving around the role of the personal.

In contrast to this, Louise Purbrick’s essay grapples with the difficulties surrounding the object as gift, including the practice of shopping for gifts. Using material from a 1990s Mass Observation directive on Giving and Receiving Gifts, she considers the reactions of respondents to the perennial problem of purchasing gifts for other people, and the struggle to select and purchase objects that can remain with the gifted as meaningful objects. The role of objects in carrying memory can become a burden, some gifts straining under the expectation that the object will be kept, loved and treasured.

This sense of embodied memory as a negative emotion also emerges from Adam Drazin’s essay on Romanian émigrés in Dublin, many of whom curtail their lifestyle to save for objects which they send home in preparation for a possibly mythical return, sometime in the future. It is particularly noticeable in his discussion of Carmen’s watch, which she hung beside the door of her spartan bedsit to act as a stark reminder of money spent unwisely in the past and a warning not to indulge in emotional connections.

The capacity of objects to hold meaning is also addressed by Jonathan Chapman, whose work strongly emphasises the importance of designing emotionally durable objects. In his essay, he considers how people retain emotional connections with their possessions over time and how this can be incorporated into the design process. Chapman discusses Emma Whiting’s concept for Puma footwear, which celebrates the process of ageing and the ‘evolving narrative experience’ manifest in the objects’ patina. Looking to the future, Chapman argues for a sustainable alternative to ‘throw away’ culture, for a society in which people value the journey that an object has taken and the memories objects hold. Durability, Chapman argues, ‘is just as much about emotion, love, value and attachment, as it is fractured polymers, worn gaskets and blown circuitry’.

Museum of Water

We were a little slow to notice the arrival of a rather interesting pop-up beneath the courtyard of Somerset House, but between 6 – 29 June, the “itinerant collection” that comprises the Museum of Water has set up home there.

The collection, which contains over 300 bottles of water collected by contemporary artist and film-maker Amy Sharrocks, provides interesting food for thought in light of our discussions last Friday, on value, authenticity, and the display potential of something as intangible as memory – in whatever form its object vessel seems to take.

All of the objects in the Museum of Water have been donated by members of the public – and although the bottles themselves are interesting in their own right, it is their contents which have the most significance. Participants responded to the call “Choose what water is most precious to you. Find a bottle to put it in. Come and tell us why you chose it. We will keep it for you.”

Amongst the responses are waters from around the world, spit, wee, condensed breath and “water from a bedside table said to be infused with dreams.” They are suffused with memories and nostalgia – a newborn baby’s bath water, baptism water, a melted snowman – and yet as they discolour and evaporate, conservation issues mean the objects themselves will shortly become memory.

Lastly, there is the issue that the significance of the waters would be entirely inaccessible were it not for the written record that accompanies them. Indeed, even with the written record, some of the offerings are deliberately meaning-less to begin with – and yet in the context of a wider whole, do they have an inherent memorial value? A signifier of what plastic bottles/ jam jars were like in 2013?

If you want to become a fossil, aim for the tar pit

Our suspicions have been confirmed: the best place to die, if you want to become a good fossil, is the tar pit. Just one of the things we learnt from listening to the excellent papers at Objects and Remembering.

We’re pleased to say that the conference was a success, with excellent papers, discussions and exuberant, if short, tea breaks. Several questions were posed and answered in different ways – what kinds of memories are evoked by objects? why do we seek to make up stories about objects (like a bracelet or a doll)? does it matter if an object in a museum is not authentic, not what it appears to be but a reproduction? what shapes the stories we tell about particular objects (political, cultural, national contexts…professional identities, childhood experiences…a romantic disposition)? how can the ways in which people relate to objects inform understanding of memory, collective memory and other forms of remembering? – This blog will continue to act as a source of information and hopefully inspiration, and any guest posts responding to the themes of the conference are very welcome.

Rosy Rickett and Felicity Winkley

Last chance to book a place!

The conference is taking place this Friday, the 20th June 2014! We’re very excited to welcome everyone and have a productive and stimulating day of papers and discussions. If you would like to come but haven’t registered yet, please take a look at the registration tab on this site. Come to the training room C1.18, the graduate school, Ellen Wilkinson. We will put up signs so it should be reasonably easy to find. Tea/coffee/lunch and a wine reception are provided for everyone who has registered…we have three places left so hurry!

Things from radiolab

The American radio show radiolab have made this lovely programme, which starts with a piece about the conflict between the presenter Robert Krulwich, who touches an old object and instantly feels a connection to the past, and his wife, who definitely does not…

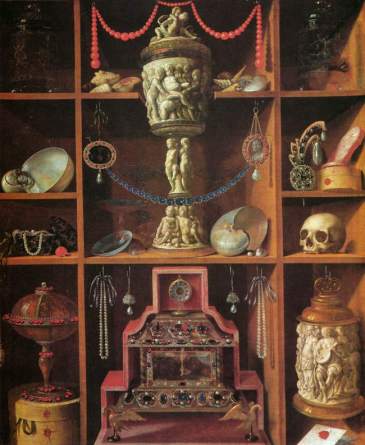

The Museum of Imaginative Knowledge

James Mansfield is an artist. One of his projects is the Museum of Imaginative Knowledge, he is not speaking at the conference but his work ties in with some of our themes. To find out more, read on.

How and why do we give value to objects? The Museum’s collection is very wide, covering the areas of local history, contemporary archaeology and classificatory art, but what unites it is finding a place for those things which do not meet the current cultural norms.

Thus there is the world’s largest one pence piece collection, and a series of jars filled with coloured water which date from before the First World War. Both (as does much of the Museum’s collections) come from the area around the English-Scottish border. And one thing which is of particular interest is the idea of memory value – that many objects have narratives which we often have no idea about.

Much of my research so far has been at Judley Hall, a decaying country house in the Borderlands. In such places, there is often a breakdown of time and space which allows the accumulation of objects which might otherwise be ignored or discarded. With around 45 rooms, Judley Hall has been inhabited by the same family for nearly 300 years. While the tapestries, oil paintings and taxidermy have all been sold off, there remains what is best described as ‘heirloom detritus’. One area of interest is the contents of drawers. This one pictured contains the remnants of the family’s map collection, as well as other assorted items. I am currently working on a detailed piece of analysis of this drawer and several others, which provide a microcosm of life in a country house in the late 20th century.

In the Museum, whether it be in person or online, I aim to present to viewers a slightly different view of the world, and the relationships we have with objects, in what I hope is an enlightening and entertaining manner. I am, of course, always interested in discussing the themes mentioned above and would be keen to undertake some kind of sustained collaborative project in the near future.

My Nana and Walter Benjamin, Or the Movement of Things

In Berlin Childhood around 1900, a series of essays written in the 1930s and unpublished in his own lifetime, Walter Benjamin uses the objects, interiors and experiences of his childhood to explore the relationship between people, memory and things. One object, the ‘reading box’, a box full of lettered tablets with which to form words, stands out:

everyone has encountered certain things which occasioned more lasting habits than other things. Through them, each person developed those capabilities which helped to determine the course of his life. And because—so far as my own life is concerned—it was reading and writing that were decisive, none of the things that surrounded me in my early years arouses greater longing than the reading box.

(As an aside, Benjamin’s reading box always reminds me of the cardboard folders with slots to put individual words in that were used to teach sentence structure in the mid-1980s. What were they called? We had individual ones and giant class ones. Evidently they – along with teaching sentence structure – are now horribly out of fashion.)

Nobody, to my mind, has ever written about things as beautifully as Benjamin does in these essays. But most interesting here is his discussion of movement. For Benjamin’s memory of the reading box is not only of the object itself, but of the repetitive movement of his hand in using it. What he seeks in his longing for the box is his ‘entire childhood, as concentrated in the movement by which my hand slid the letters into the groove, where they would be arranged to form words’.

In 1999, my Nana died. When her children were sorting through her things, my aunt gave me a small pot that had been on her dressing table. ‘She wanted you to have that’, my aunt explained, ‘because when you were little you spent hours just taking the lid off and putting it back on again’. I have a vague conscious memory of this. She kept her rings in it and I remember that I liked the sound that the lid made as it hit the base of the pot. But, mostly, it was the feeling of the two parts of the pot fitting together that I remember being most satisfying. The pot is in my living room now, on a shelf. When I look at it, I do think of Nana. But that memory is nothing compared to the feelings evoked by simply taking the lid off. For a split second, in that movement, I am five or six and I can feel the velvety fabric of the dressing table stool under my knees as I put the lid back on. Like Benjamin and his reading box, this pot ‘is thoroughly bound up … with my childhood’.

In recent years, historians have become much more open to using material sources. But I don’t think I’ve come across anyone who has yet managed to really capture the importance of movement to the way that objects are used, preserved or remembered. Why is this? Benjamin’s reading box lived in his memory; the object itself was long gone:

My hand can still dream of this movement, but it can no longer awaken so as to actually perform it. By the same token, I can dream of the way I once learned to walk. But that doesn’t help. I now know how to walk; there is no more learning to walk.

My Nana’s pot is bound up with my memory. It is not just an object, but a dynamic link with a moment, or many moments, of my own past. It is people, experience, time and emotion. Benjamin longed for a past that couldn’t be fully recovered without access to the reading box. But we, as historians, are faced with the opposite problem: we have access to the reading box, or whatever our sources happen to be, but not to the memories attached to it. They have survived, but can we really gain any sense of what they ‘meant’ to the people who have owned or used them? Or are we attempting the impossible in trying to recover a dynamic experience that has been and gone and is no more? Is there ‘no more learning to walk’?

This is a post by one of our speakers, Cath Feely, a longer version can be found here

Magical Touching

Bruce Davenport, who is presenting a paper entitled ‘Sensory Conversation partners: Objects to think, feel and remember with’, discusses the way we ‘attribute properties to objects that they actually do not possess’:

A recent edition of the BBC Worldservice programme, The Forum, focussed on ‘The real vs the virtual’. Amongst the guests was Edmund de Waal, potter and author. Bridget Kendall, the host of the programme spoke, rather gushingly, about how holding one of de Waal’s pot allowed her to commune with de Waal himself… I am being somewhat unkind as her response is not uncommon amongst people blessed with, what I would consider to be, a romantic imagination. Lots of people, historians and archaeologists being foremost amongst them, have a strong, emotional response to holding a a special object or being in a certain space. Through the object they believe themselves to be in direct contact with the person who held or made that object or who occupied that space in the past. I have to confess to a certain cynicism as I don’t share this response; however lots of…

View original post 1,129 more words